The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard

I have a thing for the Unsung heroes of history. My favorite protagonists are the humble mavericks who persist in unglamorous toil on a single task for years, usually decades. Sometimes they achieve vindication with a large, public victory and lasting glory, but this is the exception. Often, only a handful of people closest to them understand the impact had and the sacrifices made. Colonel (Ret.) James Burton is such a person. He documents his labor in The Pentagon Wars, an outstanding book that inspired a 1998 HBO movie by the same name.

The book catalogs the Reform Movement writ large and Burton’s contribution to it, while the movie focuses exclusively on the moment Burton “crosses the Rubicon,” to use his phrase, and goes to war with the Pentagon over the testing of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle [1]. Burton meticulously details how careerism, incompetence, and willful stupidity collide in a tragically ironic way to undermine the testing of the weapons meant to protect troops.

In 2023, the Bradley is back in the headlines with the United States’ commitment to send them to Ukraine. That makes now as good a time as ever to revisit the troubled history of this tank vehicle that looks like a tank but is emphatically not a tank.

Context and Background

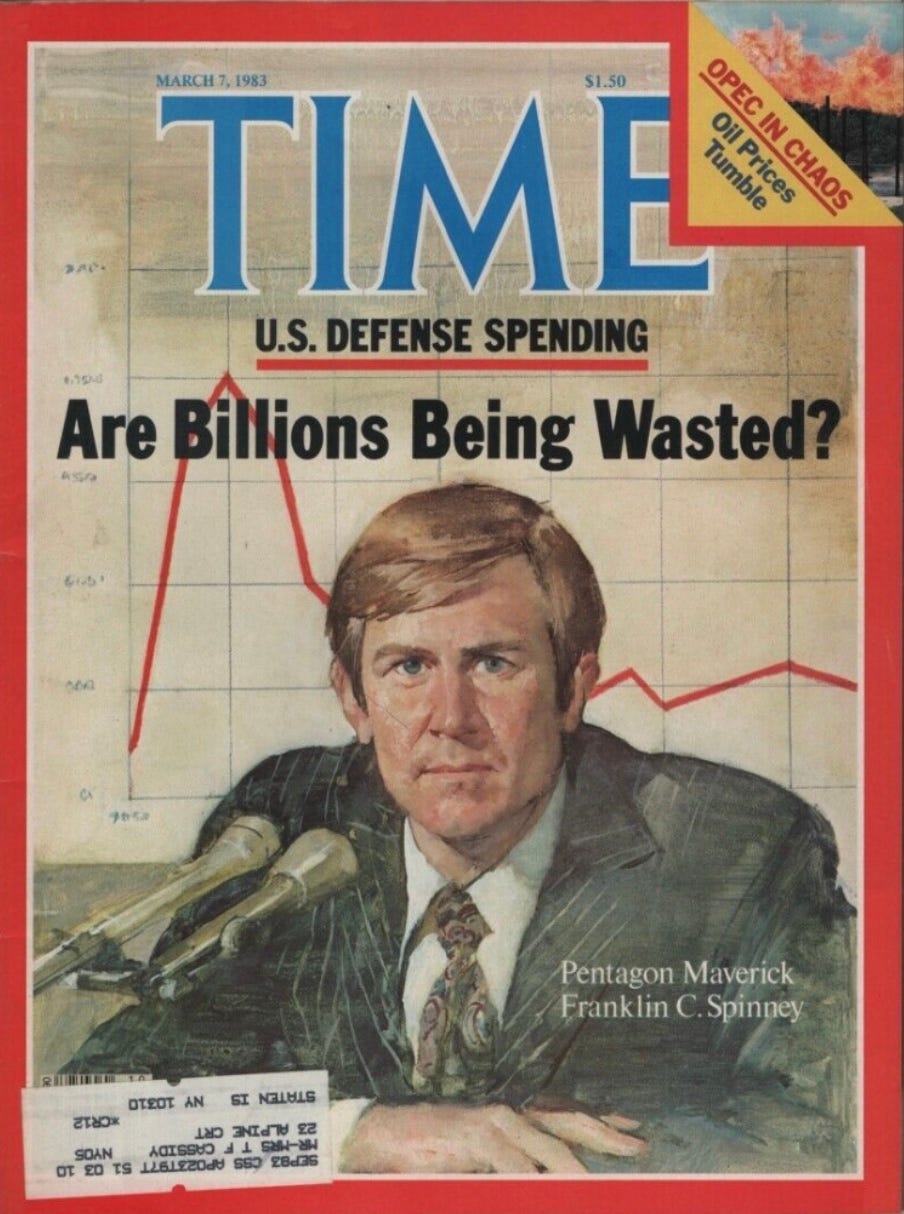

In 1983, the cover of Time magazine was splashed with the face of Chuck Spinney, a key individual in the Reform Movement, and the question: U.S. Defense Spending, Are Billions Being Wasted? It was a different era. A civil servant could become a celebrity, Time was relevant, and the public was capable of being surprised that the answer to this question could be anything other than a resounding “yes.”

The Reform Movement started by John Boyd and Pierre Sprey in the late 1970s garnered bipartisan support and led to the creation of the Congressional Military Reform Caucus. At its peak in the early 1980s, the caucus had over 100 members. Boyd and Sprey generated bipartisan support with arguments for reform that transcended mere advocacy for budget cuts. The Reformers reached the damning conclusion that “budget constraints were not the source of the problem.” No surprise there. The problems were how the military fought, the weapons they fought with, and the way those weapons were tested and procured.

Enter Colonel Burton

Burton served as the military assistant to three consecutive assistant secretaries of the Air Force across the Carter and Reagan administrations, a highly unusual tenure given that assistant secretaries typically dispense with their predecessor’s appointees. The culmination of his service was getting Congress to pass legislation to require all new weapons systems to go through live-fire test series before commitment to production. Burton advocated for realistic testing via the disastrous Bradley Fighting Vehicle. It was in development for over 15 years and started as a transport vehicle for an eleven man infantry squad. However, after design by committee, it only nominally resembled a troop transporter.

The Bradley ended up with more ammunition than any other vehicle on the battlefield, crowding out five of the eleven troops it was supposed to carry. All of this ammunition made the vehicle both a prime enemy target but also highly combustible for the troops inside, as the ammo was packed throughout the vehicle. A separate version was manufactured in parallel for the Israeli Defense Force, who demanded the fuel tank and ammo be stored in external compartments, separate from troops. Burton fought hard for this version to be used by the U.S. Army, but he was only partially successful. After years of Burton advocating, the Army moved some ammunition out of the troop compartment, but they never went so far as to store it separately. Operational testing for the Bradley consisted of water-filled ammunition and pre-selected test points. Here’s Burton on fighting for realistic testing: “By refusing to conduct realistic tests against a vehicle fully loaded with fuel and live ammunition, the Army senior leadership, in my opinion, demonstrated that it had a callous disregard for the lives of troops in the field. I could arrive at no other conclusion (pg 190).”

What’s impressive about Burton’s whistleblowing on weapons systems testing is he takes no actions stereotypical of whistleblowers, like talking to the press or selectively leaking classified information and documents. When the Bradley test data is being suppressed and manipulated, Burton writes a steady stream of reports and memos. The Xerox machine is his best friend, as he shares his documents with the maximum number of people allowed. He knows someone in the Pentagon will eventually talk to the press, thus generating immense outside pressure and accountability for accurate testing from once-revered press outlets like the New York Times and The Washington Post. Boyd is an indispensable mentor during this time. He knows that if Burton talks to the press, the establishment will have easy fodder with which to accuse Burton of publicity-seeking or unpatriotic motives. By following Pentagon procedure to the letter, Burton leaves an impeccable paper trail. It turns out having the man who invented the OODA loop as your ally is a pretty good way to out-maneuver your enemies.

At this point, the reader may be wondering in earnest just why testing and procurement are so dirty. The answer is simple: human behavior maps to the incentives an organization creates. This is not to excuse the immoral behavior of many of the actors in The Pentagon Wars, but it does explain it. Here’s Burton’s assessment:

Many incentives exist for people to usher new weapons successfully into the system. The rewards include promotions, career advancements, and the possibility of high salaried jobs with the defense industry after retirement […]. As a result of unchecked advocacy, a steady stream of weapons of unknown or questionable performances passes into military inventory. Strong resistance to realistic testing exists because such testing inevitably produces unflattering data that often inconveniences the military’s senior leaders (pg 160).

Burton’s reward for cleaning up Bradley testing was forced retirement. Technically, the Air Force tells him to transfer to Wright Patterson Air Force Base or retire. This transfer order is delivered prior to the completion of the Bradley’s Joint Live Fire tests, despite on-the-record assurances from the Undersecretary of Defense that Burton would have unfettered authority to see testing through to the end.

Then and Now

Sadly, the chutzpah of the Reform Movement now feels quaint. The F-35 replaces the Bradley as all that is wrong in defense procurement: 20 years in development, billions of overspend, unaffordable sustainment, defunct software, and an aircraft that tries to be everything to everyone [2].

The mismanagement and cronyism of weapons systems is not confined to hardware. In June 2018, the DoD launched the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC) and funded it to the tune of $1bn, dishing out large software contracts to the usual suspects (Deloitte, Booz Allen). Its purpose was to be the U.S. government’s premier example of AI development and deployment across the armed services. After a couple of years of prolific PR and spending with nothing of substance to show, the JAIC was quietly dissolved and wedged under the newly established Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office (CDAO). I am yet to see a single piece of journalism examining why the JAIC failed and who should be held responsible. What I did notice was the JAIC CTO’s smooth exit, becoming the CIA’s first ever CTO.

Today, there is a version of the Reform Movement that’s dispersed across Twitter, Silicon Valley defense companies (e.g., Anduril, Palantir), and innovation outposts across the DoD (e.g., DIU, AFWERX). While it lacks the crisp branding and centralization of Boyd’s movement, today’s movement offers ideas that are no less worthy of the brightest spotlight:

DoD should buy commercial technologies from innovative companies (often venture-backed, Silicon Valley startups) when the solution already exists rather than waste money and time building custom solutions that rarely work as advertised.

DoD needs to help non-prime companies cross the “valley of death” dividing successful prototypes and pilots from actual procurements or programs of record.

DoD needs to invest in “attritable” technologies, which are larger numbers of inexpensive, often unmanned, machines, rather than large numbers of exquisite, complex, and heavily manned machines.

On the last point, Burton and the original Reformers saw the future. The Blitzfighter was Burton’s proposal for a “small, simple, lethal, and relatively cheap airplane that would be designed for close support of the ground troops who would be engaged with Soviet tanks and more.” It would cost less than $2 million, a price point that would allow the Air Force to “flood the battlefield with swarms of airplanes.” Today, we call this concept attritable, and it’s one in which the Air Force is increasingly interested, even if they aggressively denigrated the idea in the 80s.

Many of the issues the Reformers rallied around 50 years ago still exist today. This is frustrating. Fortunately, Col. Burtons, while rare, are not extinct. Throw in the new(ish) addition of VC-funded defense tech companies looking to spearhead change, and I will optimistically state we’re looking at a lethal combination.

[1] It’s hard to summarize the Reform Movement in one or two sentences, but some key tenets were simpler, less expensive equipment, in greater numbers. Equipment should be functional and highly aligned with the warfighter’s needs rather than with a general or defense contractor’s career. If these things seem axiomatic, think again.

[2] Not that anyone has the decency to be embarrassed. The wildly popular Top Gun 2: Maverick features cute Lockheed Martin product placement and a cheeky reference as to why the F-35 can’t be used in the mission.