Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II

Freedom’s Forge is as much an invigorating ode to capitalism in the U.S. during WWII as it is an indictment of centralized planning and Communist labor organizations during the same period.

Freedom’s Forge is as much an invigorating ode to capitalism in the U.S. during WWII as it is an indictment of centralized planning and Communist labor organizations during the same period. Arthur Herman convincingly demonstrates that the biggest threat to U.S. wartime production, and by extension, our defeat of the Axis, was labor unions. That’s right: not business foot dragging, or profiteering, or even the Axis themselves, but Big Labor.

You would think that Nazis, who typify the enemy, would be sufficient motivation to get the AFL and CIO unions to cooperate in wartime production, particularly when said Nazis had just invaded Communist utopia Soviet Union in 1941. You would be wrong. “1941 was a near-record year of strikes and disputes, with more than 3,500 of them, costing 23 million man-days of labor - enough to build 124 Fletcher class destroyers (pg 151).” If not Nazis, then surely U.S. involvement post-Pearl Harbor would do the trick? Wrong again. In April 1943, John Lewis of United Mine Workers sent his workers on strike for increased wages, which halted production in Pittsburgh. I couldn’t help but experience some schadenfreude at what came next: New Deal, labor-loving FDR gets spurned by his own creation.

“When Roosevelt got the news, he exploded. He ordered the army to take over the mines and prepared a radio broadcast for May 2 appealing directly to the miners to go back to work. He was being wheeled down to the Oval Office to make the broadcast when word came Lewis had struck a deal. [… That deal only lasted until] June 19, when more than 60,000 coal miners dropped tools and went home. When Roosevelt threatened to strip the draft deferments from every mine worker, Lewis decided to halt the strike after three days (pg 246).”

Ultimately, 1943 work stoppages totaled 13.5 million man-days, and 1944 was only slightly better with 8.7 million man-days lost. “Even so, a week before D-Day, 70,000 workers were on strike at twenty-six plants in Detroit alone (pg 247).”

The U.S. is not at war today (I think), and there’s no AFL union corollary at Google (despite best efforts), but a similar dynamic is at play in the technology industry. If war starts, one of the U.S.’s greatest vulnerabilities will not be the private sector’s inability to innovate, but labor’s unwillingness to participate, often for reasons of Communist ideology cloaked in morality.

Tech workers, who naturally are well positioned to exploit the advantages of Internet virality, have hacked the need for unions. A small vocal minority organizes themselves, writes a letter to company leadership that’s inevitably leaked, and leadership caves to the demands of its Communist employees. The most notable example that’s frequently trotted out is a minority of Google employees in 2018 successfully protesting Project Maven, the Department of Defense’s marquee effort to bring AI to the warfighter. Google canceled its Maven contract, proving that less than 5% of employees have the power to hold the company hostage [1].

The chilling effect of the tyranny of the local minority is how it preempts the company leadership to make decisions that are likely to be aligned with the ideology of the day. More recently, Boston Dynamics and other robotics companies pledged to not weaponize their robotics. As is often the case with these open letters, cognitive dissonance abounds. Boston Dynamics is owned by Hyundai, which is Korea’s largest manufacturer of naval ships and artillery. Most disappointingly (and it pains me to include SpaceX, who I praise later in this review), Elon Musk announced he would not allow Starlinks to be weaponized for drone control in Ukraine [2]. Additionally, a senior SpaceX executive revealed in private conversation with me that 50% of SpaceX employees disagree with national security work, causing leadership to downplay national security contracts in internal and external communications. I’ve always been impressed with SpaceX’s ability to maintain its branding as a space company first and foremost and a government contractor second, but surely its brilliant employees can infer what the NRO satellites launching on Falcon Heavy are being used for, right?

This Kinetic Review is a negative reflection on Big Labor’s failings, but it is worth reading Freedom’s Forge to understand how a few executives from the private sector — especially former auto exec Bill Knudsen — created the proper incentives for industry to transition its production lines to be responsive to military needs. Despite the labor strikes, America unambiguously converted to the most successful wartime economy ever seen. From mass producing Liberty ships to B-29s, Herman shows it was not centralized planning by the War Production Board, but America’s free enterprise industrial system that led Knudsen to exclaim “America is in production now.”

Knudsen disabused the War Department of its notion of “M-day,” that the government could “effortlessly mobilize an economy of war with the throw of a fiscal switch (pg 341).” As is often the case when capitalism triumphs with a large Pareto improvement, the urge to rewrite history and separate the victor from the spoils is strong. And so the New Dealers moved in to credit Labor and government-directed production for the spectacular results, something not even Stalin could bring himself to do [3].

Bruce Catton, editor of American Heritage magazine, wrote in his memoirs of his years as public relations officer at the War Production Board, big business constantly got in the way by demanding it be well paid for its services and refusing to embrace a new social construct combining government, big business, and labor - an American version of socialism, one in which “labor moved up to partnership with ownership in the great U.S. industries” and government respected “its right and duty… to disregard the last vestiges of property rights in a time of crisis (pg 341).”

The media and much of the public is still allergic to industry’s success. Last month, SpaceX’s Starship, a rocket with the potential to alter the trajectory of human progress, flew for four minutes before ultimately exploding during its first test flight. Employees were holding the possibility of the rocket blowing up on the launchpad to be very real, so achieving flight was a great success. As space reporter extraordinaire Eric Berger generously engaged on Twitter with never-Elon-ers, he explained flawed test flights are part of the company’s iterative design process and will ultimately produce a functioning Starship.

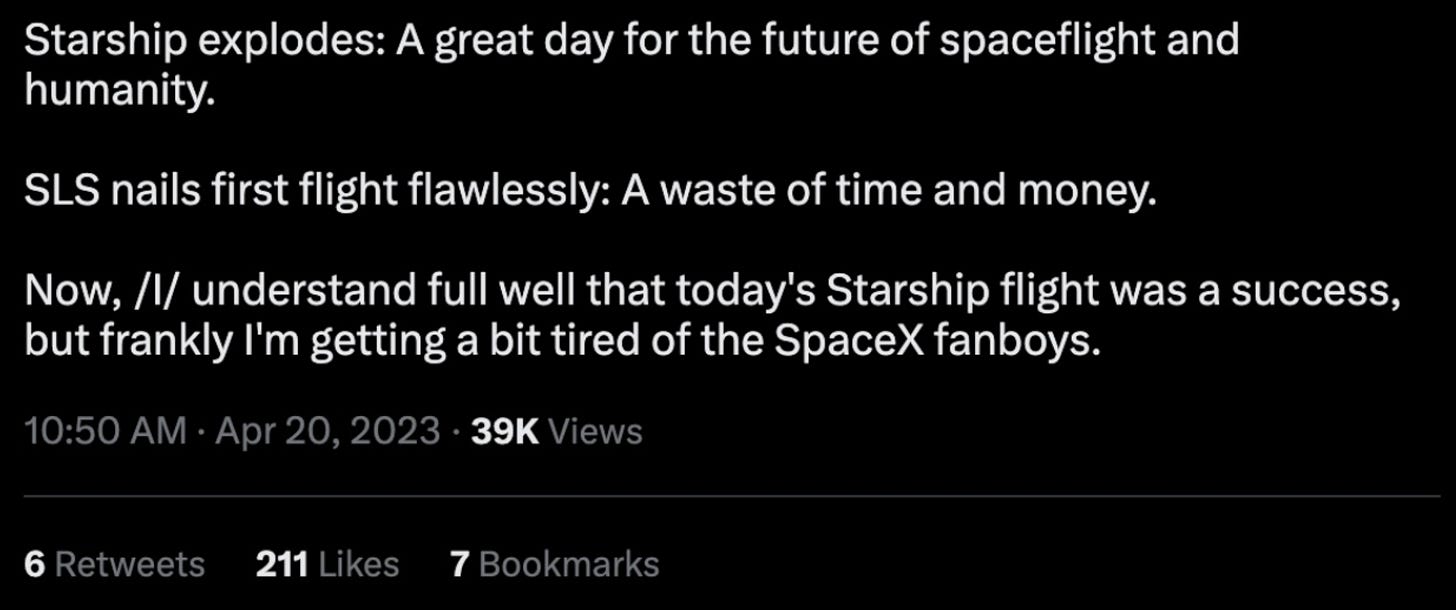

But the sentiment below was a common one (link):

Politicians joined the fray, with Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif), top Democrat on the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, remarking, “I must say, when I saw that rocket blow up, I thought, thank God there’s no people on board. Sometimes the lowest bidder is not always the best choice.”

Had rockets never flown successfully before, I could empathize with the public’s skepticism over test rockets blowing up in flight being a “good thing.” But you could not design a more perfect record of iterative design than SpaceX: In the early 2000s, their first 4 rockets exploded or didn’t reach orbit, but those tests led to the Falcon 1 and then the Falcon 9, a money-saving, reusable rocket. SpaceX has done more to advance U.S. national security and our position relative to China than any other company or government agency in the last 50 years. Truly, no good deed…

What’s more, SpaceX didn’t invent the playbook of iterative design. Reporters and politicians unequivocally criticizing the Starship launch reveal themselves to be ignorant of history or so biased in their hate for Elon and industry they are incapable of objective analysis—probably a mix of both. I’m more than happy to give the government due credit for its incredibly successful Cold War CORONA Project, which used an iterative design process to launch the world’s first spy satellites consistently and reliably. The program was not immediately successful - far from it. The first twelve launches failed in some form or another, with six of them never reaching orbit and some of them even involving rapid unscheduled disassembly.

As Rep. Lofgren mentions in the second paragraph of her bio, she worked the night shift at Eastman Kodak in the late 1960s. This was right when CORONA had hit its stride and was launching satellites multiple times a month. I wonder if she’s aware that Eastman Kodak supplied the cameras used in the CORONA satellites, and if so, how she feels having worked at a company with a heritage of “failure.”

To borrow Rep. Lofgren’s words, I must say, when I saw that rocket blow up, I thought, thank God politicians don’t run SpaceX.

[1] About 4,000 employees signed the letter out of over 98,000.

[2] Now whether this is because of Tesla’s ties to China, Russian assassination threats to Elon’s life post-Starlink donation to Ukraine, or Elon’s stated reason of preventing WWIII, we can only speculate. The outcome is the same.

[3] “When Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill first met at Tehran in 1943, Stalin raised his glass in toast “to American production, without which this war would have been lost (pg 336).””

Hello, Madeline. I just found your column. Welcome to Progress Studies!

I have been loosely affiliated with the movement for the past few years. You might be interested in subscribing to my Substack column and reading my two books on the subject. I would be happy to give you free digital copies.

I look forward to reading your future posts. Let me know if there is anything I can do to help you grow.

Freedom’s Forge is a great book. It clearly shows how economic power can be translated into military power that, in turn, influences world history.