Banished Heroes

Our best military heroes were rebels. It's time we honor that.

People who challenge the status quo are a threat to establishment institutions. Silicon Valley built its reputation by fostering these mavericks in the form of venture capital funding to founders. Militaries, as establishment institutions, have a reputation for conformity. Despite the title of Top Gun 2: Maverick, the Department of Defense (DoD) is not known for its production of contrarian individuals. Here’s Albert Einstein on the matter: “This topic brings me to that worst outcrop of the herd nature, the military system, which I abhor. That a man can take pleasure in marching in formation to the strains of a band is enough to make me despise him. He has only been given his big brain by mistake; a backbone was all he needed.”

Einstein’s caricature of the military is generally right but specifically wrong: The DoD does have mavericks; they just rarely become four star generals. And Silicon Valley’s love for its founders is not unconditional: see Apple and Steve Jobs, Uber and Travis Kalanick, etc. Much as venture capital firms sour on their founders and force them out, the DoD has an unsavory history of punitive action against the very individuals uniquely capable of building something great.

It wasn’t just Oppenheimer who got betrayed by the DoD after dedicating a significant portion of his life to protecting American lives. Let’s go through a brief tour of the DoD’s banished heroes:

Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell

Mitchell is known as the Father of the United States Air Force. A genuine war hero, Mitchell was the first American to fly over enemy lines during World War I. At the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, Mitchell commanded 1,481 American and Allied airplanes in what was the largest air operation of the war. After the war, he advocated relentlessly for investments in air power via an independent Air Force. In the process, he pissed off a lot of people, especially in the Navy, by arguing that bombers would render the battleship obsolete. Mitchell was a PR master and arranged for a highly publicized Army bomber attack that resulted in the sinking of the former German battleship Ostfriesland.

The impetus for his infamous court martial were Mitchell’s comments following the 1925 crash of the Navy airship Shenandoah. He publicly accused both Army and Navy leadership of neglecting aviation due to “incompetence, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of our national defense.” Mitchell was found guilty and suspended from active duty for five years. He resigned instead. Needless to say, he was vindicated in America’s need for an independent Air Force, but he died a decade before it was created in 1947.

Colonel John Boyd

Perhaps even more of a rabble-rouser than Mitchell, Boyd managed to escape a court martial but drew the ire of huge swaths of the DoD and its contractors. He started his career as an Air Force fighter pilot (a group hardly known for its subservience) and earned the nickname “Forty Second Boyd” for his ability to defeat any opposing pilot in less than forty seconds. His signature move can be spotted in an adrenaline-fueled sequence in the original Top Gun: Maverick lets the opposing MiG fighter get close up on his tail, ready to fire, then he pitches his own plane up at an angle, catching the air to slow him down so that the other guy flies right past him. When Maverick pitches the plane back down, he has the MiG directly in his sights.

Boyd’s fighter tactics are emblematic of how he approached life: Understand and anticipate your opponent’s decision-making process and find ways to use superior maneuverability to get one step ahead of him. All of his accomplishments used this framework, from his design of the F-16 fighter and invention of the OODA Loop to his invasion strategy for Operation Desert Storm and (my personal favorite) his bureaucratic wars with the Pentagon via the Reform Movement.

Irreverent to the core, Boyd barely made colonel and had no hope of becoming a general officer. (As a major, he once called a colonel a “lying fucker” to his face, and it was far from an isolated incident).1 Eclipsing all of his impressive material contributions is the spiritual: Boyd had a timeless morality code summed up with the phrase “to be or to do,” whereby he implored his officers if they wanted to be someone or do something.

Lieutenant Colonel James Burton

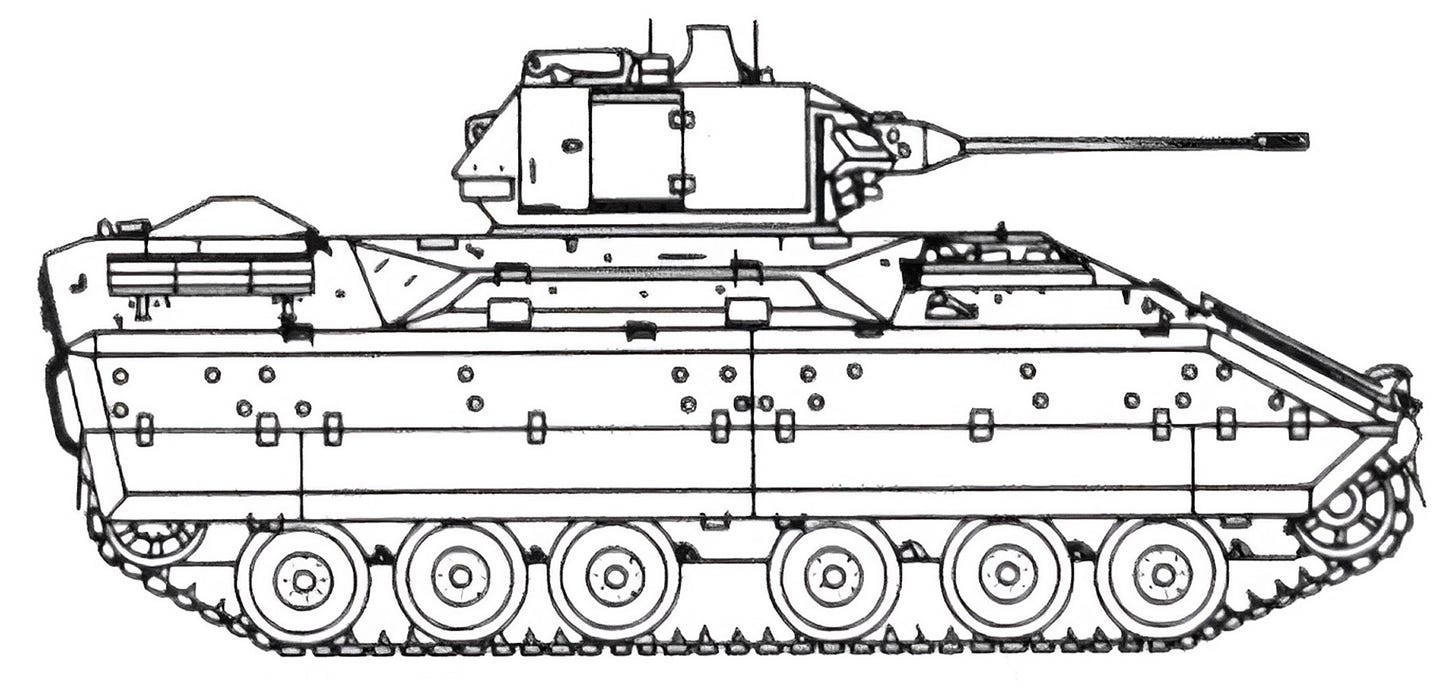

A Boyd protégé, Burton fought to put an end to the Pentagon’s corrupt processes for testing its weapons (these events are chronicled in Burton’s excellent memoir turned HBO satire The Pentagon Wars.) You wouldn’t test a bullet proof vest with a water gun, but the equivalent was happening with systems like the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. In the 80s, Burton testified before Congress multiple times. He was disgusted that the program office was prioritizing getting the Bradley into production rather than ensuring a highly combustible vehicle transporting 11 men first see conditions representative of live combat. Burton’s comments echo Mitchell on DoD’s willful negligence, “By refusing to conduct realistic tests against a vehicle fully loaded with fuel and live ammunition, the Army senior leadership, in my opinion, demonstrated that it had a callous disregard for the lives of troops in the field.”2

Thanks to Burton, Congress passed legislation requiring all new weapons systems to go through live-fire test series before commitment to production. Here’s the general in charge of the Bradley: “During Desert Storm, more soldiers' lives were saved as a result of Bradley live-fire testing than we can count.”3 Burton’s forced into retirement by the Air Force and doesn’t even make full colonel.

Colonel Drew Cukor

For a contemporary example we have Cukor, the man responsible for Project Maven, which remains one of the lone examples in all of the federal government of a functional, scaled, operational AI program. When it was created in 2017, Maven was a first-of-its-kind initiative by the DoD to deploy AI. The initial use case was assisting operators with analyzing the huge amount of drone footage from Iraq and Syria in the fight against ISIS. The program has since evolved and scaled with the changing geopolitical environment.

Maven almost immediately drew controversy when Google publicly pulled out of the program after a vocal minority within the company opposed work with the DoD. Many government program managers would have leaned away from commercial solutions after being burned by Google, but Cukor - much to his credit - maintained faith that there were Silicon Valley companies who could work with the government. Today, it’s still hard to convince the government that the private sector offers a better solution than the government building the same thing from scratch, and it certainly wasn’t any easier in 2017.

Cukor, a Marine for over 25 years, is described by his colleagues as “a classic disruptor” and “super aggressive.” As you can probably guess by now, these qualities don’t correlate with promotion. Cukor prioritized outcomes over politics and paid the price, landing a cushy private sector job as consolation prize.

Reward the Rebels

It’s difficult for any large bureaucracy to make room for independent thinkers, but the stakes are uniquely high for national security. The DoD is not leaning into its competitive advantage against any of our authoritarian foes when it crushes dissent by ensuring irreverent minds do not hold top leadership positions. There is too much focus on protecting downside and not enough emphasis on maximizing upside. Ironically, this “risk averse” attitude becomes exponentially riskier as we erode our ability to credibly deter conflict. Silicon Valley does not have a monopoly on mavericks, but it does have a much higher threshold for tolerating them.

Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War (pg 206)

The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard (pg 190)

The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard (pg 256)

Nicely done Madeline. A fun read! My personal favorite is Robin Olds. The book Fighter Pilot is a total page turner!

The true story of Drew Cukor goes much deeper than Project Maven. One day it will be told.