The Origins of Victory: How Disruptive Military Innovation Determines the Fates of Great Powers

The Origins of Victory details four iconic revolutions in military affairs and draws lessons from each to inform what the U.S. military should be doing differently.

The Origins of Victory author Andrew Krepinevich is an academic and an establishment man. Neither of these traits is inherently bad. However, in the context of writing what should be a gripping historical survey on the changing character of war with a no-punches-pulled assessment of what the U.S. should be doing differently, these traits do not correlate with success. The book reads like an academic treatise prepared for the Office of Net Assessment (dubbed the Pentagon’s think tank), where Krepinevich worked for several years under its founding director, Andrew Marshall. Here is one of Krepinevich’s climactic insights:

In summary, in each case where a military organization led the way to a disruptive shift in the competition, it enjoyed the benefit of a clear vision of the envisioned end state - what it was trying to do and how it would go about accomplishing it (pg 403).

Part I of The Origins of Victory “identifies the emerging competitive environment’s prospective characteristics,” and it includes a survey of disruptive technologies (e.g., AI, quantum, additive manufacturing). I would recommend skipping Part I, which is a long prelude to the heart of the book: Part II details four iconic revolutions in military affairs (RMA) that changed how wars were fought:

The British Royal Navy at the close of the 20th century and its reckoning with the likely obsolescence of the battleship and the potential of torpedo-armed submarines;

The German military’s development of blitzkrieg between WWI and WWII;

The U.S. Navy’s refinement of the aircraft carrier and its investment in naval aviation between WWI and WWII;

The U.S. Air Force’s precision warfare revolution leading into the Gulf War.

Where Krepinevich is spot-on is his critique that the U.S. military has failed to define and prioritize specific, operational challenges, which prevents it from experiencing the “virtuous cycle of analysis, war-gaming, field exercises, and interaction with industry important to disruptive innovation (pg 411).” As someone from industry, I can attest to the lack of a virtuous cycle, to put it mildly. New concepts are constantly pushed and branded by the U.S. military as the guiding concept going forward, but they are agnostic to the enemy and could just as easily apply to Vietnam in the 70s as China today or the Germans in WWII. See: Joint Warfighting Concept for All Domain Operations.

Because these concepts are not defined at the campaign level of warfare and are overly broad, they are not implemented successfully. Industry ensures their marketing material is aligned with what the government wants to hear, both sides get sick of the lack of progress made at the overly broad directive, and the concept develops a stigma that then warrants a rebrand. See: JADC2 to C-JADC2, kill chains to kill webs, and ABMS to C3BM.

Krepinevich’s dull writing is not his greatest sin. That distinction belongs to his harsh critique of the Defense Reform Movement of the 1970s and 80s. This critique is in direct conflict with his conclusions in his final chapter where he describes what the U.S. military needs to do differently to adopt innovation at speed and scale. Krepinevich characterizes the Reformers of John Boyd, Chuck Spinney, and Pierre Sprey as luddites who tried to stymie the precision warfare revolution of the 80s by presenting a false dichotomy to Congress and the American people: the Pentagon was buying expensive, high-tech weapons when large numbers of easy to maintain, affordable, reliable weapons would produce a more effective military and save money.

Krepinevich’s proof that the Reformers were wrong is the First Gulf War, where the F-15 performed spectacularly and accounted for a disproportionate number of kills. Sprey was critical of long-range fighters, while Boyd was overly indexed on maneuvering air combat fighters. The latter was influenced by his experience in the Korean War, and he aggressively advocated for the F-16 over the F-15. What Krepenivich omits is that Boyd was central to the design of the F-15 (originally the F-X, which Boyd vociferously opposed) and its shift towards a lighter, more agile, less complex fighter. And as the most widely operated fighter jet in the world, the F-16 is hardly irrelevant. Sprey was also extremely supportive of the A-10, which itself performed very well in the Gulf War. The A-10 remained so popular that there was genuine debate over if it could provide most of the functionality of the F-35, and it’s only in 2023 that its retirement has begun.

Thematically, the Defense Reform Movement could not have been more correct, something Krepinevich refuses to concede. The Reformers were not luddites - they were against high complexity weapons systems, not high technology weapons systems (War on the Rocks recaps the distinction nicely).[1] Chuck Spinney’s prophetic Defense Facts of Life remains as relevant as ever and predicts high complexity/high technology procurement disasters including but not limited to: the Army Future Combat Systems, the F-35, the Zumwalt, the Littoral Combat Ship, OCX ground stations, etc. The Reform Movement is consistent with Krepinevich’s critique of U.S. military procurement:

Not only is the U.S. military slow to field new capabilities, but it has also compiled an unenviable record of “failure to launch” systems that have stumbled through their development process only to be canceled for being impractical, far over the initial cost projections, or both (pg 440).

The Pentagon risks operating off “program momentum:” simply continuing to field capabilities that are moving through the production pipeline. Yet these programs were initiated years, and in some cases well over a decade ago, when the United States’ geopolitical position was far more favorable, and the threats it confronted far less advanced (pg 439-40).

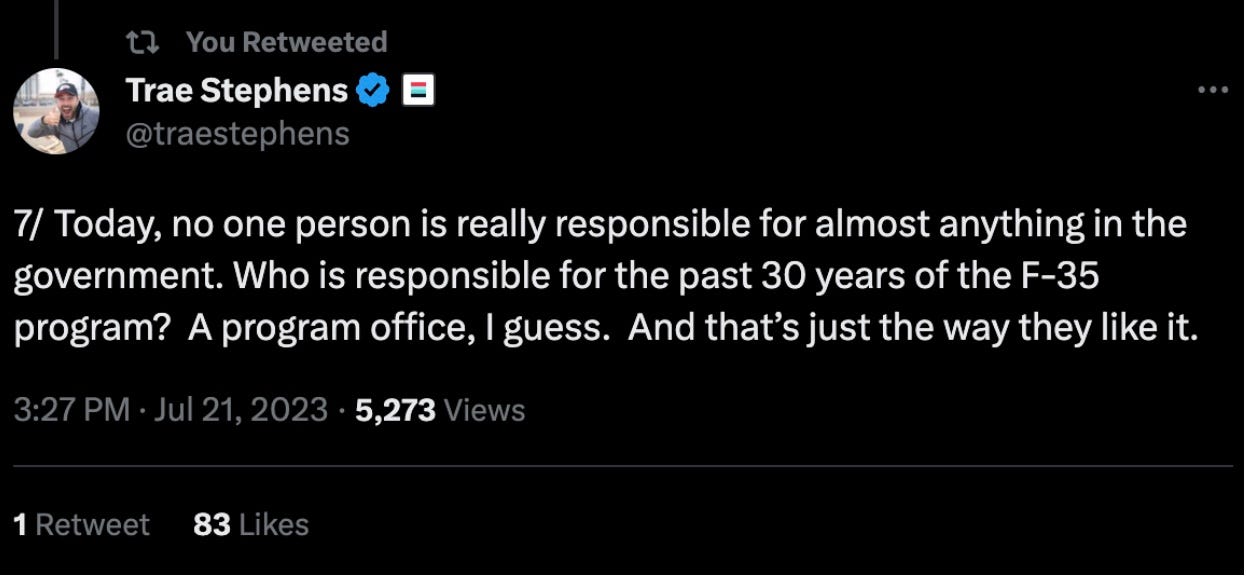

Krepinevich then proceeds to pose the questions: “Which capabilities merit continued production? Which should be canceled?” For Krepinevich, these don’t need to be rhetorical questions, and this is where he should use his status as an insider to take an opinion not only on what programs should be canceled but also who should be held accountable for their failures.

Krepinevich is also the co-author of The Last Warrior: Andrew Marshall and the Shaping of Modern American Defense Strategy. On innovation, Krepinevich arrives at the following conclusion following his tutelage under Marshall:

No methodology or set of rules could ensure innovation would succeed. Peacetime military innovation appeared to be a highly contingent endeavor in which factors such as visionary leaders with the talent to operate effectively in bureaucracies, and plain good luck could play - and often had played - decisive roles (221).

In other words, he’s a believer in the Key Man theory. Great. Let’s find and raise our key (wo)men in industry and government. As much as people must be held accountable for failures – again, in both government and industry – so people must be incentivized to grab glory and be properly exalted when they have succeeded. I want a 2,000 word Time profile on a career bureaucrat or an up-and-coming Colonel. While Krepinevich and I may disagree about who counts as a visionary leader (e.g., Boyd), we are in vigorous agreement about the ability of the individual to affect outcomes, something that sadly feels out of vogue in many circles.

But maybe we’re making progress. After all, a three star general did interview Palmer Luckey at a recent U.S. Space Force Reverse Industry Day. The latter wore his signature flip flops and Hawaiian shirt and held the audience rapt with his equally signature irreverent commentary. It was the highlight of the event.

[1] “[Defense Reform Movement] has been interpreted as an argument for smaller budgets, or as an argument against advanced technology. This view is totally incorrect. We need more money to strengthen our military; however, we believe that unless we change the way we do business, more money could actually make our problems worse. Inextricably combined with the broad issue of how we spend our money, is the issue of how we should use our superior technology - specifically, should we continue to increase the technological complexity of our weapons? Do the positive qualities of high complexity weapons outweigh their negative qualities? Advanced technology and high complexity are not synonymous.” - Defense Facts of Life.