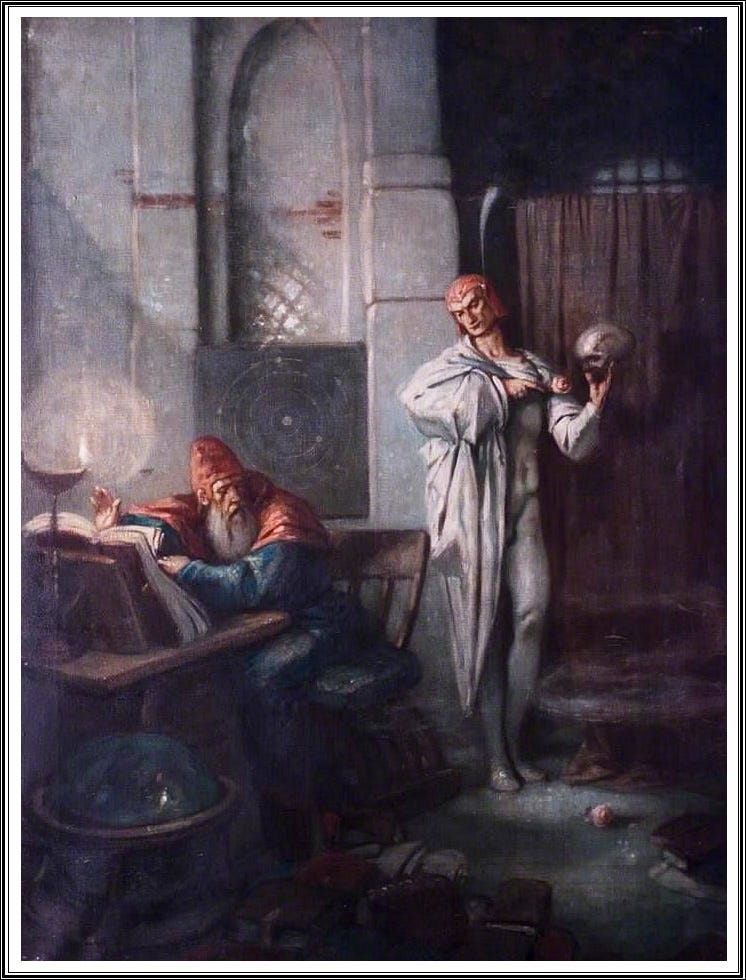

Rejecting Our Faustian Bargain

We cannot allow innovation to be driven exclusively by crisis.

The U.S. military-industrial complex has made a Faustian bargain. It hasn’t sold its soul for infinite knowledge, but it has become dependent on crisis to fuel innovation. World War II and the Cold War were required to forge the arsenal of democracy, build the Pentagon, split the atom, field radar, operate SLBMs, launch earth observation satellites, get to the moon, achieve Mach 3 flight, and deploy stealth technology.

This is neither a good nor necessary bargain.

Maybe you disagree and don’t find anything wrong with the current arrangement. You might be thinking the Department of Defense (DoD) exists to wage war and respond to enemies, so it’s appropriate that innovation happens when the threat is at our doorstep (or our Allies’), and it languishes otherwise.

But relying on war to motivate progress is not an optimal strategy. It is a fundamentally reactive posture that imposes a ceiling on American excellence by positioning it relative to a competitor. That competitor could be a pacesetter, but they could also be mediocre, in which case America is dragged down to the lowest common denominator. For a sports analogy, consider Usain Bolt. He broke both the 100m and 200m world records, twice. He wouldn’t have broken either a second time had he been content to just beat the second-place finisher, because the second-place finisher was slower than Bolt’s previous personal best.1

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union was a technological pacesetter (or we thought they were, which for practical purposes had the same effect). After the fall of the Soviet Union, the U.S. engaged in conflict with various Balkan and Middle East states who were not pushing the boundaries of innovation. These conflicts lowered our standards of excellence. In this period, the U.S. accelerated drone technology – a lead we subsequently squandered2 – and advances in the military applications of AI, but in comparison to the 1940s-80s, not much happened.

To the point of lowered standards: a much-touted success story during the Global War on Terror was the rapid acquisition of mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicles (MRAPs) to replace the Humvees that were insufficient protection from the IEDs killing and mutilating our troops at a horrifying rate. Ultimately, the DoD shipped 27,000 MRAPs for $40 billion in what was “the first major military procurement program to go from decision to full industrial production in less than a year since World War II.”3

However, this accelerated acquisition occurred only after requests for MRAPs had been delayed two years because none of the Services wanted to foot the bill for a vehicle that was not the long-term replacement for the Humvee. Secretary of Defense Gates himself had to reach down and issue a directive making the MRAP program the highest priority DoD acquisition program, providing it legal priority over other military and civilian production programs. The MRAP acquisition was a “success” in a sea of dysfunction.

All of this is indicative of a scary trend: the activation energy required to respond to crises is increasing at the same time our country’s industrial capacity is weaker than it has ever been.

The DoD is hyper-focused on China as a pacing threat. All eyes are on a possible invasion of Taiwan by 2027. But if that’s really what the U.S. is concerned about, we should be acting with a sense of urgency. As I’ve previously written with my colleagues:

When WWII started, America did not have an industrial base equipped for the fight. Fortunately, we had a luxurious eighteen months to ramp production under Lend-Lease, supply the Allies, and build the arsenal of democracy while we were still at peace. The U.S. should similarly be using the Ukraine war as the canary in the coal mine to ramp production full-scale. Instead, we’re immobilized.

A popular topic of debate right now concerns the U.S.’s ability to pull off a WWII-esque production coup. Greg Ip’s recent WSJ piece provides a good summary of the current situation: production has shifted to East Asia and “government’s emphasis on lowest-cost production discourages the remaining contractors from having the extra capacity needed to surge production.” Our inaction suggests a complacency that because we did the improbable during WWII, we can do it again. But as any financial advisor will tell you, past performance is not an indicator of future results.

There is also a lot of low hanging fruit representenative of a military-industrial complex that is deeply unserious when it comes to driving progress. The Navy will not get all the Super Hornet jets it needs from Boeing because of data rights disputes. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and the U.S. Space Force are squabbling about who has the authority to purchase commercial satellite imagery. The Israeli variant of the F-35 is demonstrating a higher operational tempo than the U.S. can manage, in part because Israel negotiated independence from the main F-35 program, allowing the IAF to directly test and ship software. And on and on.

It's hard to imagine a break-glass, wartime general allowing any of these issues, which amount to middle school politics, to get in the way of outcomes. But why wait until wartime to solve problems we can fix today?

If the military-industrial complex is only capable of innovating during wartime (and even that premise is questionable) and is dysfunctional during peacetime, this bodes poorly for progress writ large. The U.S. government has a unique role to play in progress by seeding capex intensive and often highly regulated technologies that will not otherwise make it to a commercial market. For some of the world’s most impactful technology, the U.S. government will be the first but not the biggest customer. The integrated circuit is the best example of this. Minuteman and Apollo were critical early programs, but chip demand for personal computing was soon a much bigger market than defense. The Space industry today is around the same stage as the integrated circuit was in the early 1960s.

Now, the U.S. government should not seed industries it has no use for, but for certain technologies, it is the pacesetter on progress. It is therefore unacceptable to have stagnation just because the American people no longer practice duck-and-cover drills.

I concede there are attributes of crisis that make it easier to innovate. Lives are on the line. People are motivated to work harder than they ever have. Unnecessary regulations are ignored. Peacetime generals are replaced with wartime generals. The most talented people are more likely to be given responsibility over the most political people. The boat gets rocked.

But ultimately, rejecting our Faustian bargain does not require breaking the laws of physics. It requires embracing the intrinsic value of progress as a good in and of itself. Some will dismiss this sentiment as idealistic, but dedicating ourselves to a vision of a better future is the only path forward. We have evidence this is possible. I mention SpaceX a lot, but it’s one of the few organizations – public or private – to achieve wartime results in peacetime.

We don’t need a pandemic for the FDA to get out of its own way in accelerating vaccine approval.

We don’t need to wait for the electric grid to go out before we embrace nuclear power.

We don’t need Xi Jinping to visit San Francisco before we clean up the streets.

In 2024, let’s fight for peacetime progress.

Later on in Bolt’s career, Yohan Blake ran faster than Bolt’s first 200m world record. However, this was not the case when Bolt set the current 200m world record in 2009.

Shyam Sankar writes “General Atomics invented the modern drone in the 1990s with the Predator. A Noycian figure would have seen the vast potential for not only commercial drone applications but also the consumer market. Instead for decades that vast R&D focus of these platforms was locked by Govt R&D programs. And with great effect. But without any American prosperity that should have followed GA owning or spinning out a Commercial subsidiary that should have been the DJI of America. Instead the vacuum let DJI fill it to serve CCP civil-military fusion aims. Now the hobbyist consumer’s drone purchase funds CCP R&D against America.”

Gates, Robert. Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War (pg 122)

Madeleine - I agree with you completely!! Enjoyed the article!!

Thank you for a great article. If we want peace, and we do, we must prepare for war. Being prepared will save both lives and dollars.

I saw you reviewed the excellent Freedom's Forge. Have you read Safi Bahcall's "Loonshots"?