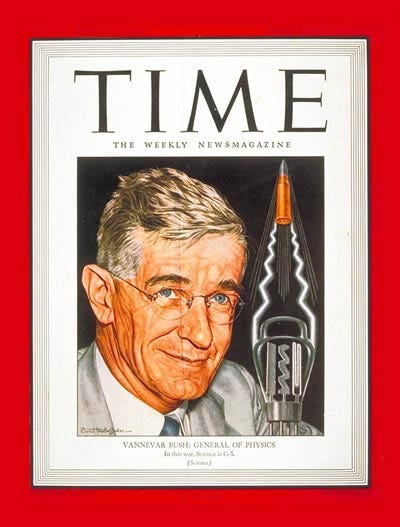

What would Vannevar Bush look like today?

As the role of government in innovation changed, so did our attitudes towards innovators.

Imagine living during the golden age of your profession. Like being an English Admiral in the late eighteenth century, a painter in Italy during the Renaissance, or a philosopher in ancient Greece. Vannevar Bush was a perfect man of his time: a government-minded technocrat who led and shaped American institutions during their golden age in the mid-twentieth century.

Largely at the direction of Bush, the federal government transformed during WWII into the primary funder and coordinator of technological innovation. Bush led the newly formed Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), which was responsible for all wartime R&D. Here, he initiated the Manhattan Project and oversaw advances in radar and the mass production of penicillin.

Under his watch, OSRD dollars poured into universities for basic and applied research, which became intertwined with the government in a new and lasting way. University labs sprung up, like MIT’s Radiation Laboratory or “Rad Lab,” and Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. These connections to academia hearken back to Bush’s pre-war career as an MIT professor and dean of its School of Engineering. Even Bush’s commercial endeavors, like co-founding Raytheon, have tentacles to academia and government.

His influential manifesto written at the end of the war, Science: The Endless Frontier, provided the intellectual foundations for the formation of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1950, which ultimately was just one of several government agencies funding R&D. By 1964, federally funded R&D as a percent of GDP reached its apex of 1.86%. Bush was no longer a big time government bureaucrat at this point, but his fingerprints are all over the continuously expanded role of government and universities supporting the post-Sputnik space race. As Brian Balkus writes,

Over 20 percent of Caltech’s budget in 1964 came from the DoD, and it was only the 15th largest recipient of funding; MIT was first and received twelve times as much money. The U.S. military and scientific elite were enmeshed in a way that had no parallel in the rest of the world then or now.

But the government would soon begin ceding its role in innovation. Conservative free market policies in the 70s and 80s, like the 1981 Research and Development Tax Credit, and the emergence of venture capital facilitated this trend. By 2020, U.S. businesses were outspending the government on R&D by 3.5x.

As the role of government in innovation changed, so did our attitudes towards innovators.

If Vannevar Bush had published Science: The Endless Frontier in 2023 rather than 1945, he would have been pilloried. We know this because Marc Andreessen provides us with a pretty good controlled experiment with his recently published The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.

Techcrunch asked “When was the last time Andreessen talked to a poor person?” NYTimes called it a “horrifying, silly vision.” Washington Post, a “self serving cry for help.” Gizmodo rather confusingly labeled it a “Unabomber-style manifesto.” For comparison, here are excerpts from Bush’s and Andreessen’s pieces:

Without scientific progress no amount of achievement in other directions can insure our health, prosperity, and security as a nation in the modern world. - Bush

Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential. - Andreessen

Bush feels unusually anachronistic for an historical figure. He regarded himself as a “link between the President and American science and technology,” and he enabled innovation by aligning institutions as an insider. Today, confidence in American institutions is at an all time low. Venture funding is our contemporary engine for prosperity, and it often necessitates subverting existing structures. Our modern Bush-ian figure would have to be an outsider from the private sector.

To me, Elon Musk most closely represents the modern manifestation of Vannevar Bush.

From a character perspective alone, many will bristle at the unsightly comparison. Bush was a dedicated public servant, son of a pastor, humble to a fault, a family man wedded to the same woman his whole life. Musk is a megalomaniac, public philanderer, and Twitter shitposter. A parody of Silicon Valley.

He is also a reflection of our society and very much a Man of Our Time. Where Bush was an atomic era industrialist, Musk is a digital era industrialist who understands that the most interesting innovations in the physical world still require approval from the government, whether it be voluntary or coerced.

It is a feature - not a bug - of Musk that he is a world shaper at odds with the very institutions he needs to work with. SpaceX had to sue NASA for the right to compete. And SpaceX won! Bush wouldn’t approve of the government breaking the law by excluding commercial companies.

Musk revolutionized launch economics with SpaceX, which is the single greatest improvement to our national security posture since Bush’s Manhattan Project. I shudder to think how our space capabilities would compare to China right now had the United States continued to rely on Lockheed Martin and Boeing’s United Launch Alliance for pioneering rocketry.

Now Musk is tunneling through Vegas with the Boring Company, ushering in the era of the electric vehicle with Tesla, and building human-machine interfaces with Neuralink.1 While these endeavors require contact with institutions at the federal, state, and local level, Musk is not an institutions man.

To be clear, this approach has its faults. By always treating the government as an adversary, Musk has made things harder on himself. The Justice Department’s lawsuit against SpaceX for discriminating against refugees and asylum seekers feels vindictive. Musk publicly complains about FAA regulations impeding launch progress, but the FAA has done a pretty good job of enabling Musk’s experimental launch regime. And his donation of Starlinks to Ukraine and subsequent refusal to allow the Ukrainians to use them to launch an offensive in Crimea was a decision viewed by many military leaders – rightly or not – as an ugly attempt to privatize DoD policy.

Bush’s approach also had its limitations. The academia-industrial complex he enabled has stagnated. The grant system and PhD-to-tenure pipeline is dysfunctional.

It’s simplistic to say Bush unified government, academia, and business. These are three very heterogeneous sectors whose relationships to one another have always had tension. He did, however, demonstrate a functional model of leadership worthy of inspiration, if not quite emulation.

With Neuralink (most recently valued at $5 billion) Musk shares an interest with Bush in the link between human consciousness, memory, and computing. Bush wrote second very influential essay, As We May Think, where he conceives of the Memex, a device “in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.” The Memex is a concept which influenced future hypertext systems and inspired computer scientists.